Rose Schreiber

Ceramic Art

Artist Statement

Like the shadow of an idea not yet fully thought, a shadow

from the future… the ecological thought creeps over other

ideas until nowhere is left untouched by its dark presence.

Timothy Morton, The Ecological Thought

The process of decay is at the same time a process of

crystallization, that in the depth of the sea, into which sinks

and is dissolved what once was alive, some things "suffer a

sea-change" and survive in new crystallized forms... as

"thought fragments," as something "rich and strange”...

Hannah Arendt, Illuminations

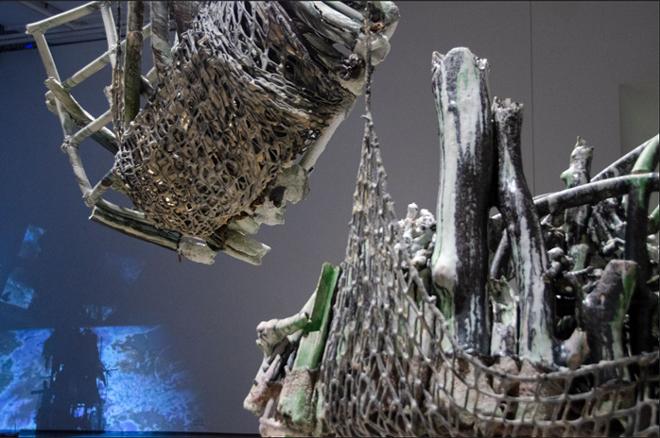

Deathly assemblage of sticks. Procession of snapped limbs, full of channels and holes, cloaked

under foamic glass skin. Branches that pitch and lean into one another. Look close: they are

floating. They are barely touching-of-the-ground. Swept up by a current of peroxide, they have

amassed as driftwood on a phantom bank. Such alluvial accretiveness, such natural disrepair, that

you wonder: are they a made thing or a found thing? Were they pulled, as ghostly detritus, from

the silty floor of a salt lake? Or were they authored in some wholly human way—created in human

image, suffused with human meaning?

These ceramic sculptures are made by applying clay slip to dead organic matter and then burning

that organic matter away. Materials such as roots and branches, bark, rope, string, fabric, and

netting serve as molds. Once fired, these molds turn to ash, their life forms preserved as static,

hollow voids. They become, in a sense, palimpsests—empty signs of their former selves. Both

absent and present. Fired in undulating beds of sand, many of them hover just above the ground.

This hovering calls to mind spirits, shadows, ghosts. A weather of elegy surrounds them, has

perhaps washed them ashore.

Shadow and substance. Netting and mesh. These are the dueling, metastasizing visual metaphors

this work engages—metaphors that speak, not simply within the narrow purview of ‘nature’ and

‘the environment,’ but to questions about how we apprehend knowledge and other beings in the

broadest sense. The larger ecocritical significance of these metaphors lies in how they position and

conceptualize the non-human, material world: whether they impose upon it a static, orderly, and

anthropocentric worldview, or whether they drive us to recognize interconnection, contingency,

and enmeshed subjectivities.

Click to view A ceramic sculpture made up of a bending central grid, netting, and hollow branch forms. The sculpture barely touches the pedestal—its entire weight is maintained by the tips of a few branches. The sculpture is glazed in drippy green, black, white, and blue glaze. Full-Screen

Click to view A ceramic sculpture made up of a bending central grid, netting, and hollow branch forms. The sculpture barely touches the pedestal—its entire weight is maintained by the tips of a few branches. The sculpture is glazed in drippy green, black, white, and blue glaze. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature Is There No Such Thing // Ceramic // 28" x 42" x 20”

Click to view A close-up image of the grid and hollow branch forms. The glaze is foamic in some places, satin in others. Full-Screen

Click to view A close-up image of the grid and hollow branch forms. The glaze is foamic in some places, satin in others. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature Is There No Such Thing // Ceramic // 28" x 42" x 20”

Click to view Close-up image of netting that is sustaining the sculptures. A black polyester net is coated in yellowish beige latex. Full-Screen

Click to view Close-up image of netting that is sustaining the sculptures. A black polyester net is coated in yellowish beige latex. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature To The Dogs // Ceramic, polyester net, latex

Click to view Close-up installation image of sculptures suspended in latex - coated nets. Full-Screen

Click to view Close-up installation image of sculptures suspended in latex - coated nets. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature To The Dogs // Ceramic, polyester net, latex

Click to view Close -up installation image of the latex - coated net passing through one of the holes of the grid. Branches are moving in one direction, the grid in another, and the latex net in another. Full-Screen

Click to view Close -up installation image of the latex - coated net passing through one of the holes of the grid. Branches are moving in one direction, the grid in another, and the latex net in another. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature To The Dogs // Ceramic, polyester net, latex

Click to view Installation image of two sculptures on pedestals. A blurry human visitor is seen in the background. One of the sculptures consists of vertically arranged hollow branches, glazed in white and pink tones. The other sculpture is a algae -green grid. Fabrics and hollow branches are interlaced with the grid. Full-Screen

Click to view Installation image of two sculptures on pedestals. A blurry human visitor is seen in the background. One of the sculptures consists of vertically arranged hollow branches, glazed in white and pink tones. The other sculpture is a algae -green grid. Fabrics and hollow branches are interlaced with the grid. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature To The Dogs // Ceramic

Click to view Installation image of a white branchy sculptures suspended in the air. They are held up by metal. Full-Screen

Click to view Installation image of a white branchy sculptures suspended in the air. They are held up by metal. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature To The Dogs // Ceramic, cables, metal rods

Click to view Installation image of a grouping of three large-scale grid sculptures, two of which are suspended by latex-coated nets. In the background, two more sculptures are visible on pedestals. Full-Screen

Click to view Installation image of a grouping of three large-scale grid sculptures, two of which are suspended by latex-coated nets. In the background, two more sculptures are visible on pedestals. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature To The Dogs // Ceramic, cables, metal rods, latex, polyester netting

Click to view Wide-angle installation image of the entire show. Pieces are seen suspended from the ceiling, others placed on pedestals. Full-Screen

Click to view Wide-angle installation image of the entire show. Pieces are seen suspended from the ceiling, others placed on pedestals. Full-Screen

Rose Schreiber // Nature To The Dogs // Ceramic, cables, metal rods, latex, polyester netting